Shulamith Firestone and Me

Reflections on TFG #4 "Community" & memoir writing class

In 1989, when I was 23 years old, I lived with my infant daughter in Santa Cruz, in a house that was sectioned into apartments. It was terribly hard to find a place to rent. I had been very near leaving town when an excited woman and man came up to me, asking if I was still looking for a place to rent. She had a large bedroom and kitchen, with a small bathroom in between, on the first floor. Would I like to move into the bedroom? (She would be moving into the kitchen, which I could also still use.) I would!

I came to the West Coast from the East Coast: at first to San Francisco where I had a few friends living in a warehouse in the Mission, but I was unable to find housing there. Then I went to stay with my friend Britney in a pickers shack/artist colony by the seaside, outside of Santa Cruz, until her film maker boyfriend came back and kicked us out. Finally my daughter and I lived in a welfare hotel in town, for two months, searching for housing and almost finding it until a few collective houses told me “no children allowed.” I was really getting desperate. I had come to the West Coast for a better life after all.

Once settled down into that rambunctious run-down house on Locust Street—where rent was just about my entire welfare check (I think I had 20-35 dollars left over)—I could concentrate on building piles of books up around my bed; and push the stroller to the nearby Evergreen Cemetery, to look for banana slugs and let my newly walking child stretch her legs in beautiful gothic splendor. Or push the stroller down town, through a tropical walk way (it felt to me, Santa Cruz so beautiful with plants) at the end of my street, until we got to the difficult part with the steps. Where I would have to pick up the stroller and hoist it up or down often with her in it, or holding onto her so she didn’t topple. Then past the library and the lemon trees, to the playground. Or the down town outside mall area. The main hang out.

I had thought I would find more of a home with my Peace March friends (the ones who had come from California) or my DC and Boulder friends, who were now living in San Francisco. But instead I started making my own new little life, eventually finding more of a home with the younger punk rockers who hung out on “the bench.” Many, but not all, of them with hippy parents. And in general more child-friendly, and willing to hang out with a young mom and her daughter. Drinking, cavorting, joking around, and killing time.

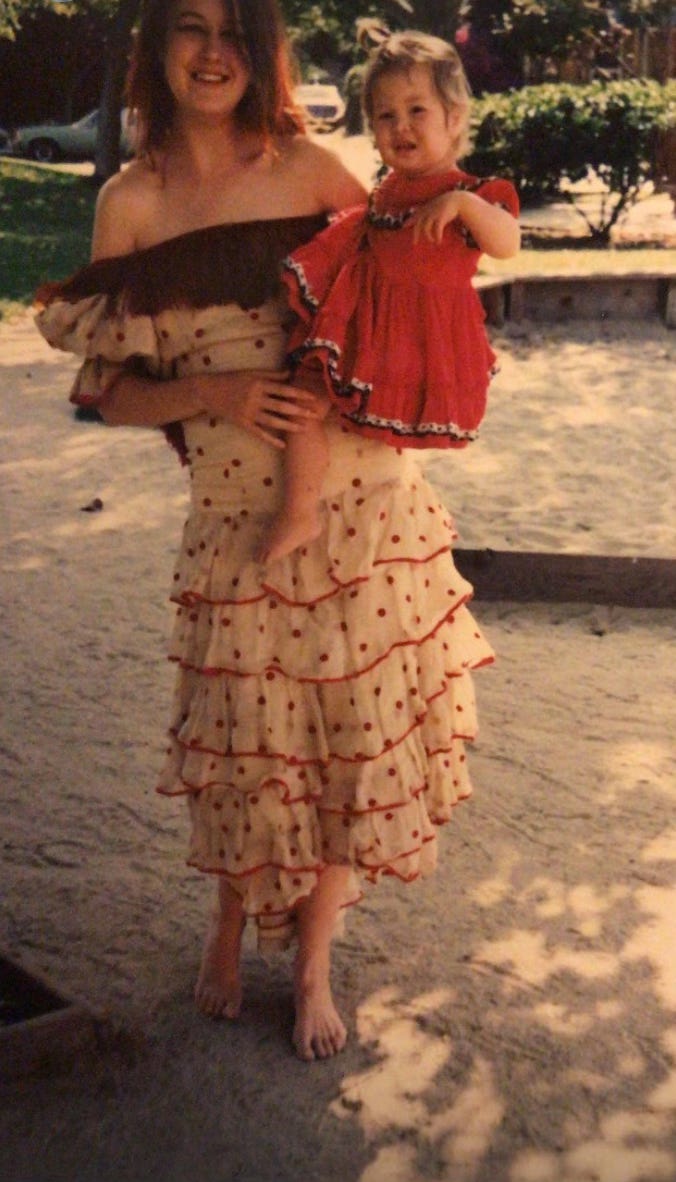

At that time my hair was very long and red. It was my crowning glory. I have a photo of me, in a white and red polka dot flamenco dress that I bought at a yard sale from an aged dancer, who danced in Spain. Bethezda, my eccentric neighbor, lived on the other downside apartment of the house, with her son Mars. She had given us a tiny vintage red dress, as well, that my daughter wore in the photo. My first real love of my life, the boyfriend I met a few months after moving in the house, took the photo of us. It probably was the peak of my attractiveness.

I felt sheltered in that town, despite the counterculture casualties, single moms with hard lives and left over dregs of the 60s, dreams that didn’t work out, drugs and mental illnesses, the “wing nuts” as they were called. One could walk barefoot, like I was in that photo. Or go topless, like my neighbor, who gardened with her small, sagging (I thought at the time), breasts exposed in jeans, high heels, a cigar, and pitchfork, in the front yard. Hang out, laugh— although things weren’t perfect, in its own way it was kind of sweet. With free organic produce in the free box outside the co-op, fragrant jasmine growing all around town, and sea anemones in the tidal pools at the beach.

It was time to figure out what next. How could we live? And I raise a child? I came to California for more radical community, perhaps a collective house, or to connect with the friends that I had made in my earlier travels. But I was finding life as a radical mother was not very easy. Long red hair or no.

And so I turned to books. One of the early books I remember reading was "The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution" (1970) by Shulamith Firestone. Like the early French feminist, Simone de Beauvoir, she found motherhood a drag and children enslaving. And so thought it better not to have children, instead of changing the world to be better for children and mothers. But somehow, Shulamith made me smile. Her solutions were so wild. No more pregnancy. Everyone will come from artificial wombs. And not in a creepy Brave New World way. But just so it can be equally distributed between all, men and woman, and the accident of the genitals you are born with no longer defining your whole life. The book had been written a while ago, it seemed. (These 60s and 70s which we were living in the fallout of, and in a more conservative and also punk rock rebellious 80s). But her chapter on abolishing childhood and the nuclear family was within my interests. There wasn’t much written on the topic elsewhere. She felt that children must be free for women to be free, and vice a versa. That childhood was a social concept, used to justify the nuclear family, also a recent invention.

Nothing I would use to quote, though, in the first zine I would put out a year and so later. And not in The Future Generation #4 “Coming Together”, where I come to a conclusion that I would then dwell in for decades—that we need more community. If we are to be liberated, if we are to change the world for the better, if we are to resist oppression and do better in our own world building, we really, really, need more community for this.

In the recommended reading list for a memoir class with Ariel Gore, I see Shulamith’s name as editor in the New York publication, of an essay where the origins of the feminist slogan “the personal is political” comes from. This makes me think of her again.

Revisiting my zine every Throwback Thursday (on substack) I’ve been googling past influences and seeing how they are linked, what they continued to do, how these thoughts hold up. It’s been interesting. I came across a video of Shulamith Firestone, and I have to tell you she does seem cool. She seems fresh, like those girls who hold their own, for their whole weird bright slightly neurodivergent selves. I can see why I liked her. Surely Shulamith has held up better, I said to myself, than Germaine Greer! (Germaine Greer, at age 95, has been publicly transphobic for a while now.) Greer who I found so fresh, and loved so much, during that time - that I printed the entire first chapter “A Child is Born” of her book, “Sex and Destiny: The Politics of Human Fertility” in issue #4 of my zine). Shulamith with her wild technological dreaming of escaping the prison of gender. Her big open radical mind. The art school girl. I know she ended up dying alone, a rather famous article written about her, The Death of a Revolutionary by Susan Faludi, that kind of summed up the failure of the feminist movement of the time, to make and create a better way; and keep more free ways of living for and with each other. I knew she’s written one more book, towards the end of her life.

Community, I think. Community while aging, needed more than ever, more than even the support of the young, perhaps.

I’d ordered “Airless Spaces” about her time in the mental health facility, when I had found out about it, a year or so ago. But I hadn’t cracked it open yet. I wondered if I could read it before the essay was due? I decided to read and flip through it. My initial reaction was disappointment. (I would like to take more time with the book still.)

What had I hoped for? Some kind of scathing intellectual expose on madness and institutions? I felt her voice… similar to what it had been, bursting with unique real life and interesting detail, but it also was dampened down, so worn and beaten, so tired and full of stories of “losers” and “suicide” which is a topic I would love to read about from her. But her tone was so lackluster and meandering, to me. Depressing.

She had been supported to write and publish this. Supported by a group of women, brought together by her psychiatrist, who also dispersed. And in the end her body wasn’t found for a month.

Community, I think. Community while aging, needed more than ever, more than even the support of the young, perhaps. This whole life we have had to build and are missing. Sadly, sourly, alone, so alone, it feels in this society. And how do we deal with aging family issues? And our own issues. Glancing over this book today, as I live in a row house I own alone in Baltimore, and thinking about my parents in their 80s in North Carolina, alone together; my dad diagnosed with Alzheimer's three years ago, isn’t helping.

After I spend time with her last book, I think I might not write about Shulamith as my topic in memoir class due today.

I keep researching her anyway. At the end of the book she talks about her brothers at first hidden suicide, and how their parents lied that he had died in a car crash not by a self inflicted bullet, as what first sent her to the psychiatric hospital. In googling I find her sister says it was her father’s death—her father that she had so struggled with, perhaps informing the whole chapter on abolishing childhood—that finally broke her mental health for good.

When I was pregnant I used to say that I would never push a baby stroller, but instead would have a helium balloon to cary my baby around in.

I read her book was written about in the Introduction: Breathing in Airless Spaces: Disability Studies and Mental Health as a break through, not sad. “Diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, she spent time in and out of psychiatric hospitals on involuntary committals. However in the early 1990s, a makeshift network of women organically emerged to help Firestone survive. Encouraged by their support, Firestone wrote Airless Spaces, a series of vignettes about her life in and out of hospitals and about the community of disabled people who were her friends and acquaintances. This collection is divided into three sections inspired by Firestone’s life: Mad Community, Mad History, and Mad Survival.”

I see her father fled Nazi Germany and later liberated a concentration camp. He was very sexist to her and they had big fights at home. I learned this from the writing of her youngest sister Tirzah Firestone, who is 70 and still alive. She wrote a book “Wounds into Wisdom: Healing Intergenerational Jewish Trauma” that looks good.

Most of my research on books that influenced me lead to other books I want to read reflecting on them. These days I have books in various piles, as well as bookshelves, around the house, instead of just around my bed. Usually the writer, my original influence, is the better writer, the bigger influence upon society, but it’s interesting to learn more and trace the things branching out, and changing.

I’m glad her sister is alive and working on breaking generational trauma.

Yes there is much problematic about Shulamith. I hadn’t remembered the racism and the homophobia that went on in further chapters. Sophie Lewis wrote a wonderful article called “Shulamith Firestone Wanted to Abolish Nature—We Should, Too. Revisiting her brilliant, irritable, deeply flawed manifesto in the pandemic.” Which ever so slightly rings a bell to me about Chapter 5: “Racism: The Sexism of the Family of Man.” “In her deconstruction of the “myth of the Black rapist” in Women, Race and Class, Angela Davis politely summarizes this theoretical clusterfuck thus: “Firestone succumbs to the old racist sophistry of blaming the victim.” Spillers is less polite: “Is this writer doing comedy here, or have we misread her text?” (paragraph 4)

When I was pregnant I used to say that I would never push a baby stroller, but instead would have a helium balloon to cary my baby around in. In this same way, I was excited by Shulamith’s audacity to dream up new solutions. The utopian dreaming and pushing for change. The disruption of fucked up society as we knew it and willing to curse and stand up and do something about it. The trail blazer. The theorist. She was 25 when she wrote that book. And of course, those who do make progress in some ways, do not in others, and are products of their time. Every book that taught me something new also had problematic parts to it. There was no perfect book nor person.

Reading the whole chapter by Germaine Greer, I still think it’s a good chapter. The critique of “the anti-child thrust of the western lifestyle” is important to me. I went on to read other books about the history of childhood. As well of talk to grown children of negligent hippy parents and the damage they had in their life from not being protected as children enough.

How do I end this in talking about Shulamith and me? Sometimes people are prettier when they are younger. But aging is so important too. And not everyone gets to do it. It's its own struggle. We all live in the fallout of radical ideas and movements. Some seem to blossom well into it. Others are renting a one-room apartment, using the small kitchen stove door as a drop down table for painting with my daughter, and arguing with me about who inherits the typewriter from the neighbor across the hall, a young student who I adored, after her suicide. Writing letters to the editor and entertaining their circle of aged cronies. Or driving around in an old school bus whose folding doors are built to represent a bible opening.

Some get weird, so weird, Germain Greer, goddamn it. But perhaps in the weirdness of these trail blazers, they came up with some goddamn good ideas or open the way for more ideas to blossom, out of concrete. They hit their heads first so its softer for us to bust through. But they also, in their freedom, come up with and echo some bad shit too. These theorists, these think-a-lots. Its a lot to consider it all. I come up with no clean final thoughts. I just realize, I still like thinking about it all. Even as my mental powers are waning, although I have more free time for it and have found that more free time is not all I need to be a good writer.

We have books, and thoughts, and stories, to connect us. Let us be kind to each other. And more just. Not racist. Not homophobic. Not Transphobic. Not ableist. Protect children from abuse as well as let them grow in freedom. And learn. And do better! Focus on practical things. But this connective tissue of radical elders, some turning out better than others with a re-examination. Its still our history, at least some of us, of trying for better; and failing. But I, for one, will keep trying. And reading. And learning. And looking. And searching to figure out what the hell to do.

Sometimes solutions are small: small as just to go read at the cafe. And bump into a friend. And hear her story, of her road trip with her mother, after her father’s death. And be glad to be in the sun, listening, and learning, and nodding my head, with my beautiful friend. Just like when I was a new mother. Other peoples stories, what they are doing with their life, in this new stage of life I’m in too, help.

To try to not be alone. Because being alone is so bad for you. Even if many of us can’t help but be too alone in our lives, our whole lives long, it seems. And that is the personal and the political. Because this being too alone is an epidemic. And the state profits off our isolation.

Recently I had my hair cut short by a wonderful hair dresser, who is also a DJ. She wanted to check in with me before cutting my undyed (I stopped dying my hair around 40, wanting to see the natural color while I still had it) thick long hair to so short as I asked. If there was anything wrong. Or I just wanted a change. I laughed for her concern. “Oh yes I just want to try something new!” I go long and short, back and forth, restless in my hair styles, but also love my natural undyed colored hair so much. (While still dabbling with wanting to dye it! Blue I think.) Its subtle but it sparkles in the sunlight. I think I actually am a dirty blond-brown honey red head. My hair is taking a long time to grey and has a rather prominent white streak at the part in the front, where my hair flips over.

My daughter, the little girl in the red dress, is now a woman of 36 years old, with brightly colored hair, tattoos, and piercings.

I think I look better, in my late 50s, then younger me thought I would. There is memory loss and high cholesterol (something I never imagined) but “sagginess” isn’t a concern. (I mean, as I sag also, but I mostly don’t care. My body doesn’t feel a collection of sagginess, but of fat and muscle and bone and just as wonderful, and awkward, as it ever was.) My aging self, just like my search for freedom, isn’t what I imagined. And the world while worsening, isn’t as far gone—think Mad Max, circa 1979—as I had actually imagined it would be by now. I have been living from a very apocalyptic place, most of my life. The ongoing issue of feeling outside of things, of feeling my needs not being met enough, and pervasive loneliness (from my birth, when I was separated from my mother after they knocked her out on drugs, onwards) does wear me down. It also feels amazing I am still here, like I’m a video game that is so many levels along!

My daughter, the little girl in the red dress, is now a woman of 36 years old, with brightly colored hair, tattoos, and piercings. A great artist, kind, playful, joy-seeking human, and interesting thinker exploring generational trauma, healing journeys with therapy and meds, medicinal marijuana to treat her aches, and what makes people tick. She works as a Sous-chef, with a bandana over her hair, often a role model to the younger folks in the kitchen, as she loves food, teaches them, and endeavors to disrupt capitalism and patriarchy and leave better systems behind her.

Life in America is often out of balance. Some have too much. And many have not enough. Such is the case with time to yourself. Even though I have prioritized fighting for time for myself, as a writer, I also feel too much destructive loneliness within it. This can be hard to understand who don’t have enough time alone, but I think folks that are more isolated, perhaps disabled or aged, and in different situations know the effects that feeling too alone can have on you. Just like water and oxygen, the things you need to flourish, can also be the things that kill you, if they are in too great amount.

In Susan Faludi’s “Death of a Revolutionary” it said that “social defeat” is a factor in causing schizophrenia. If I’m being honest, I have to admit that I have felt social defeat, in my younger values of anarchism, and many of my dreams, as well. Some say loneliness can be the cost for a creative life, for being different, for being avant guard, for taking time for yourself to invest in your dreams. It’s good to remember an aspect of the search for truth can be loneliness as well. So it’s not seen as a cautionary tale. The older woman who dies all by herself. We all have to die sometime, after all. As Tirzah said, also in Faludi’s article, at her eulogy:

"When Tirzah’s turn came to give a eulogy, she addressed Ezra. “I said to him, ‘Excuse me, but with all due respect, Shulie was a model for Jewish women and girls everywhere, for women and girls everywhere. She had children—she influenced thousands of women to have new thoughts, to lead new lives. I am who I am, and a lot of women are who they are, because of Shulie.’”

Shulamith has many daughters. I think of my daughter’s stories, and I realize-although I will not be a biological grandmother-that I too have many grandchildren. The search for comrades and liberation continues.

P.S.

I was one year old, when the movie I liked so much “Shulie” was shot. And in the year of Shulamith's death (2012) my second book, “Don’t Leave Your Friends Behind: Concrete Ways to Support Families in Social Justice Movements and Communities” co-edited with Vikki Law, had just come out. How earnestly I once worked to build stronger community support for caregivers and children, when my daughter became a teenager and I felt old/privileged enough to escape the in-the-trenches childrearing years myself, with so many actions, discussion, brainstorming, zines, and book submissions gathered from many different people. In this way perhaps, a link to Shulamith’s work as she believed that women and children’s liberation was linked and I believe everyone’s liberation is linked with everyone else’s. I have to laugh when I read reviews of our book, as most people complain but also point out things they liked about the book. I love these reviews! No book was ever written before, or after, in such a way. And it was after all, just a beginning, of gathering and expanding on solutions, once you understand there is a problem. Still I think it's a helpful great book. We were always treated kindly in person and given many opportunities to speak, share stories, give input, and listen. Creating supportive community continues to be a problem. As does understanding our issues. And working towards survival and social support.

We didn’t get a lot of press but local criticism too, as the one radical local reviewer wrote she wished we would have gone deeper in theory. But compiling this stuff, it would be lost if not in a book. And we are only humans not perfect. We did it!! Nothing else was or is out there the same. It’s a start.

I had never heard about Shulamith like so many others ( I mean I avoid-ed white feminist thinkers like covid) so thank you for introducing her to me. It has me going down quite the rabbit hole. I did also want to say that I am grateful for your voice- honest, direct, curious, self critical and critical and also for the ways you practice because you do practice the world you want to live in. I have witnessed it and been a beneficiary of it and it is inspiring.

China, thank you for this great piece. Your thoughts and writing are flowing so beautifully these days - lean and limber and gorgeous and inspiring. I had never heard of Shulamith, and like you I love nothing more than to discover new voices and forgotten books. Amen to everything you say - and I might steal the suicide cover-up for the novel I’m going to try and finish in Ariel’s upcoming Fall Manuscript Class. Big ❤️